The DDB file (DFPT)#

This notebook explains how to use AbiPy and the DDB file produced by Abinit to analyze:

Phonon band structures including the LO-TO splitting in polar semiconductors

Phonon fatbands, phonon DOS and projected phonon DOS

Born effectives charges \(Z^*_{\kappa,\alpha\beta}\) and the dielectric tensors \(\epsilon^{\infty}_{\alpha\beta}\), \(\epsilon^{0}_{\alpha\beta}\)

Thermodynamic properties in the harmonic approximation

In the last part, we discuss how to use the DdbRobot to analyze multiple DDB files and perform typical convergence studies.

Note

AbiPy provides two different APIs to produce figures either with matplotlib or with plotly. In this tutorial, we will use the plotly API as much as possible although it should be noted that not all the plotting methods have been yet ported to plotly.

AbiPy uses a relatively simple rule to differentiate between the two plotting libraries:

if an object provides an obj.plot method producing a matplotlib plot, the corresponding

native plotly version (if available) is named obj.plotly.

Note that plotly requires a web browser hence the matplotlib version is still valuable if you need to

visualize results on machines in which only the X-server is available.

In AbiPy versions greater than 0.9, it is possible to try converting matplotlib figures produce by plot methods

into Plotly figures using the optional argument plotly=True, although the result is not always guaranteed.

Suggested references#

Integration with the materials project database#

AbiPy, pymatgen and fireworks have been used by Petretto et al. to compute the vibrational properties of more than 1500 compounds with Abinit. The results are available on the materials project website. The results for the rocksalt phase of MgO are available at https://materialsproject.org/materials/mp-1009129/

To fetch the DDB file from the materials project database and build a DdbFile object, use:

ddb = abilab.DdbFile.from_mpid("mp-1009129")

Remember to set the PMG_MAPI_KEY in your ~/.pmgrc.yaml as described

here

How to create a DdbFile object#

Let us start by importing the basic AbiPy modules we have already used in the other examples:

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore") # Ignore warnings

from abipy import abilab

abilab.enable_notebook() # This line tells AbiPy we are running inside a notebook

import abipy.data as abidata

import os

# This line configures matplotlib to show figures embedded in the notebook.

# Replace `inline` with `notebook` in classic notebook

%matplotlib inline

# Option available in jupyterlab. See https://github.com/matplotlib/jupyter-matplotlib

#%matplotlib widget

To open a DDB file, use the high-level interface provided by abiopen:

ddb_filepath = abidata.ref_file("mp-1009129-9x9x10q_ebecs_DDB")

ddb = abilab.abiopen(ddb_filepath)

A DdbFile has a structure object:

print(ddb.structure) # Lengths in Angstrom.

Full Formula (Mg1 O1)

Reduced Formula: MgO

abc : 2.908638 2.908638 2.656848

angles: 90.000000 90.000000 120.000000

pbc : True True True

Sites (2)

# SP a b c

--- ---- -------- -------- ---

0 Mg 0 0 0

1 O 0.333333 0.666667 0.5

Abinit Spacegroup: spgid: 0, num_spatial_symmetries: 12, has_timerev: True, symmorphic: False

and a list of q-points associated to the dynamical matrix \(D(q)\):

ddb.qpoints

<abipy.core.kpoints.KpointList at 0x7f5627910f80>

At this point, it is worth mentioning that Abinit takes advantage of symmetries to reduce the number of q-points as well as the number of perturbations that must be computed explicitly within DFPT.

The set of q-points in the DDB file (usually) does not form a homogeneous sampling of the Brillouin zone (BZ). Actually they correspond to the sampling of the irreducible wedge (IBZ), and this sampling is obtained from an initial q-mesh specified in terms of divisions along the three reduced directions (ngqpt).

ddb.qpoints.plotly();

Note that the DDB file does not contain any information about the value of ngqpt because one can merge an arbitrary list of q-points in the same DDB. The algorithms implemented in anaddb, however, need to know the divisions to compute integrals in the full BZ. This is indeed one of the variables that must be provided by the user in the anaddb input file.

AbiPy uses a heuristic method to guess the q-mesh from this scattered list of q-points so that you do not need to specify this parameter when calling anaddb:

ddb.guessed_ngqpt

array([ 9, 9, 10])

Warning

If the guess is wrong, you will need to manually set this attribute to the correct value of ngqpt before

invoking anaddb from python.

This could happen if, for instance, you have merged DDB files computed with \(q\)-points that do not belong to same grid.

To test whether the DDB file contains the entries associated to \(\epsilon^{\infty}_{\alpha\beta}\) and \(Z^*_{\kappa,\alpha\beta}\), use:

print("Contains macroscopic dielectric tensor:", ddb.has_epsinf_terms())

print("Contains Born effective charges:", ddb.has_bec_terms())

Contains macroscopic dielectric tensor: True

Contains Born effective charges: True

Metadata are stored in the header of the DDB file. AbiPy parses this initial section and stores the values in a dict-like object. Let us print a sorted list with all the keys in the header:

from pprint import pprint

pprint(sorted(list(ddb.header.keys())))

['acell',

'amu',

'dfpt_sciss',

'dilatmx',

'ecut',

'ecutsm',

'intxc',

'iscf',

'ixc',

'kpt',

'kptnrm',

'lines',

'natom',

'nband',

'ngfft',

'nkpt',

'nspden',

'nspinor',

'nsppol',

'nsym',

'ntypat',

'occ',

'occopt',

'rprim',

'spinat',

'symafm',

'symrel',

'tnons',

'tolwfr',

'tphysel',

'tsmear',

'typat',

'usepaw',

'version',

'wtk',

'xred',

'zion',

'znucl']

and use the standard syntax for dictionaries to access the keys:

print("This DDB has been generated with ecut", ddb.header["ecut"], "Ha and nsym", ddb.header["nsym"])

This DDB has been generated with ecut 44.0 Ha and nsym 12

We can also print the DDB object to get a summary of the most important parameters and dimensions:

print(ddb)

# If more info is needed use:

# print(ddb.to_string(verbose=1)

================================= File Info =================================

Name: mp-1009129-9x9x10q_ebecs_DDB

Directory: /home/runner/work/abipy_book/abipy_book/abipy/abipy/data

Size: 218.73 kB

Access Time: Thu Jan 15 12:16:35 2026

Modification Time: Thu Jan 15 12:15:08 2026

Change Time: Thu Jan 15 12:15:08 2026

================================= Structure =================================

Full Formula (Mg1 O1)

Reduced Formula: MgO

abc : 2.908638 2.908638 2.656848

angles: 90.000000 90.000000 120.000000

pbc : True True True

Sites (2)

# SP a b c

--- ---- -------- -------- ---

0 Mg 0 0 0

1 O 0.333333 0.666667 0.5

Abinit Spacegroup: spgid: 0, num_spatial_symmetries: 12, has_timerev: True, symmorphic: False

================================== DDB Info ==================================

Number of q-points in DDB: 72

guessed_ngqpt: [ 9 9 10] (guess for the q-mesh divisions made by AbiPy)

ecut = 44.000000, ecutsm = 0.000000, nkpt = 405, nsym = 12, usepaw = 0

nsppol 1, nspinor 1, nspden 1, ixc = -116133, occopt = 1, tsmear = 0.010000

Has total energy: False

Has forces: False

Has stress tensor: False

Has (at least one) atomic perturbation: True

Has (at least one diagonal) electric-field perturbation: True

Has (at least one) Born effective charge: True

Has (all) strain terms: False

Has (all) internal strain terms: False

Has (all) piezoelectric terms: False

Has (all) dynamical quadrupole terms: False

If you are a terminal aficionado, remember that one can use the

abiopen.py script

to open the DDB file directly from the shell and generate a jupyter notebook with the -nb option.

For a quick visualization script, use abiview.py.

Invoking anaddb from the DdbFile object#

The DdbFile object provides specialized methods to invoke anaddb and

compute important physical properties such as phonon band structures, phonon DOS, etc.

All these methods have a name that starts with the ana* prefix followed by a verb (anaget, anacompare).

These specialized methods:

build the anaddb input file

run anaddb

parse the netcdf files produced by anaddb

build and return AbiPy objects that can be used to plot/analyze the data.

The python API is flexible and exposes several anaddb input variables. The majority of the arguments have default values covering the most common scenarios so that you will need to specify these arguments explicitly only if the default behavior does not suit your needs. The most important parameters to remember are:

ndivsm: Number of divisions used for the smallest segment of the high-symmetry q-path.

nqsmall: Defines the q-mesh for the phonon DOS in terms of the number of divisions used to sample the smallest reciprocal lattice vector. 0 to disable DOS computation.

lo_to_splitting: Activate the computation of the frequencies in the \(q\rightarrow 0\) limit with the inclusion of the non-analytical term (requires {{dipdip@anaddb} 1 and DDB with \(Z^*_{\kappa,\alpha\beta}\) and \(\epsilon^{\infty}_{\alpha\beta}\)).

The high-symmetry q-path is automatically selected assuming the structure fulfills the conventions used by Setyawan and Curtarolo but you can also specify your own q-path if needed.

Plotting phonon bands and DOS#

To compute phonon bands and DOS, use:

# Call anaddb to compute phonon bands and DOS. Return PHBST and PHDOS netcdf files.

phbstnc, phdosnc = ddb.anaget_phbst_and_phdos_files(

ndivsm=20, nqsmall=20, lo_to_splitting=True, asr=2, chneut=1, dipdip=1, dos_method="tetra")

# Extract phbands and phdos from the netcdf object.

phbands = phbstnc.phbands

phdos = phdosnc.phdos

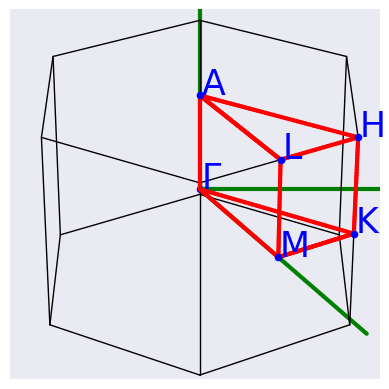

Let us have a look at the high symmetry q-path automatically selected by AbiPy with:

phbands.qpoints.plot();

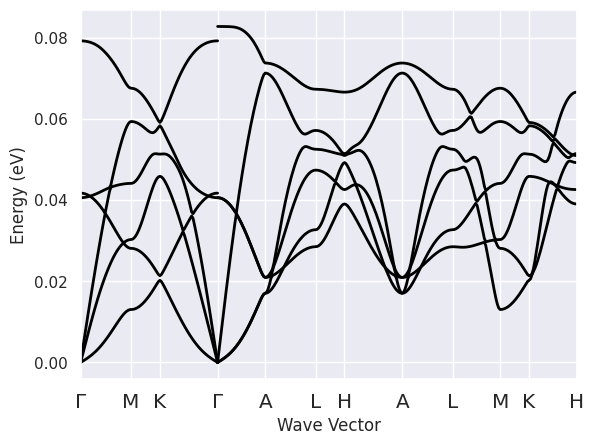

and plot the phonon bands along this path with:

phbands.plot();

phbands.plotly();

Note the discontinuity of the optical modes when we cross the \(\Gamma\) point.

In polar semiconductors, indeed, the dynamical matrix is non-analytical for \(q \rightarrow 0\).

Since lo_to_splitting was set to True, AbiPy has activated the calculation of the phonon frequencies

for all the \(q \rightarrow \Gamma\) directions present in the path.

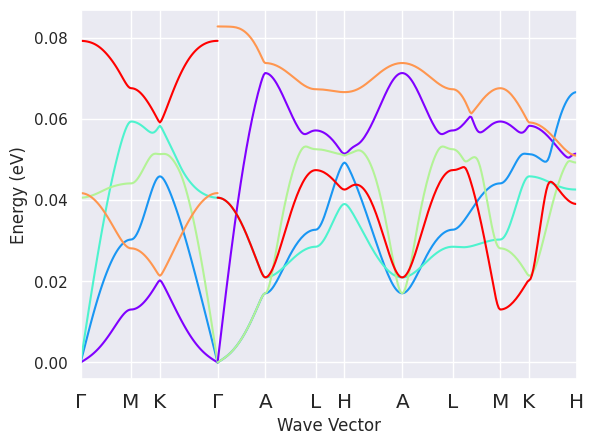

There are several band crossings and anti-crossings hence it’s not easy to understand how the branches should be connected. Fortunately, there is a heuristic method to estimate band connection from the overlap of the eigenvectors at adjacent q-points. To connect the modes and plot the phonon branches with different colors, use:

phbands.plot_colored_matched();

Warning

This heuristic method may fail so the results should be analyzed critically (especially when there are non-analytic branches crossing \(\Gamma\)). Besides, the algorithm is sensitive to the k-path resolution thus it is recommended to check the results by increasing the number of points per segment.

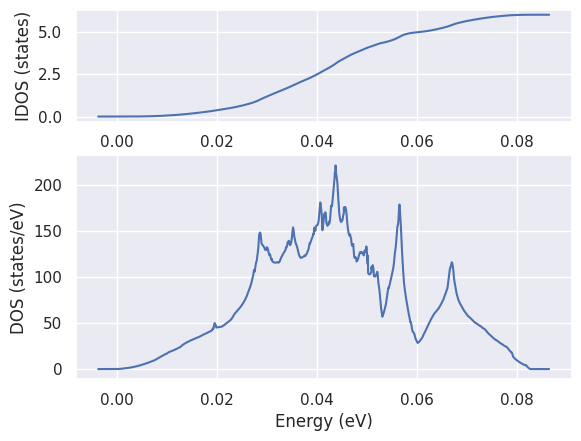

To plot the DOS, \(g(\omega)\), and the integrated \(IDOS(\omega) = \int^{\omega}_{-\infty} g(\omega')\,d\omega'\), use:

phdos.plot();

Note how the phonon DOS integrates to \(3 * N_{atom} = 6\)

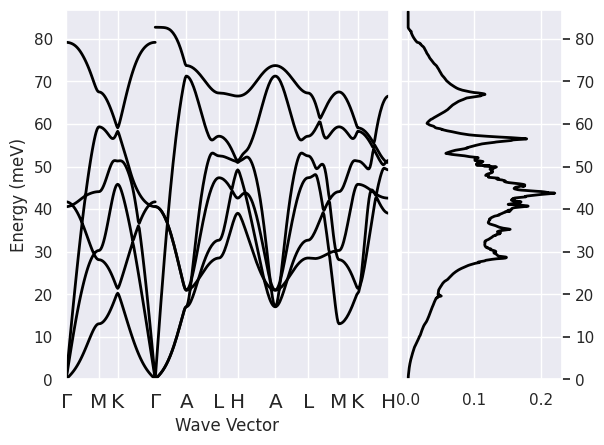

To plot the phonon bands and the DOS on the same figure use:

phbands.plot_with_phdos(phdos, units="meV");

phbands.plotly_with_phdos(phdos, units="meV");

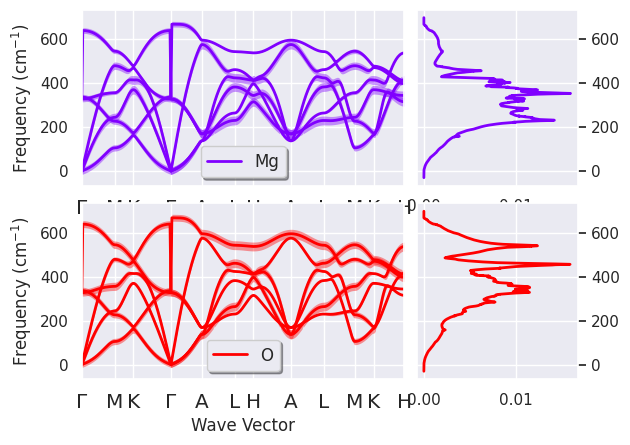

Fatbands and projected DOS#

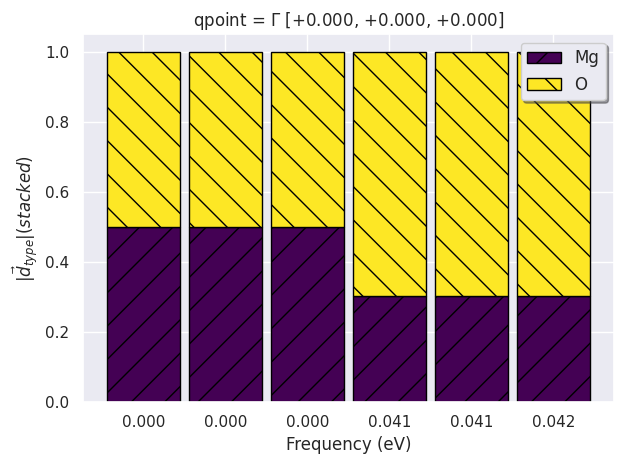

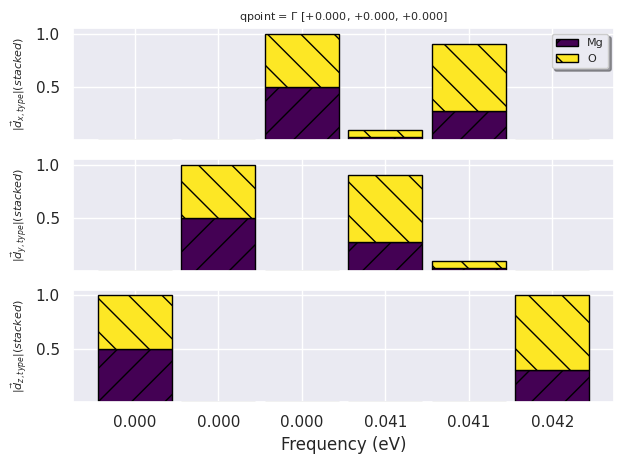

The phbands object stores the phonon displacements, \(\vec{d}_{q\nu}\) and the eigenvectors, \(\vec{\epsilon}_{q\nu}\)

obtained by diagonalizing the dynamical matrix \(D(q)\).

We can therefore use the eigenvectors (or the displacements) to associate a width to the different bands (a.k.a. fatbands). This width gives us a qualitative understanding of the vibrational mode: what are the atomic types involved in the vibrations at a given energy, their direction of oscillation and the amplitude (related to the displacement).

# NB: LO-TO is not available in fatbands

phbands.plotly_fatbands(use_eigvec=True, units="Thz");

To plot the fatbands with the type-projected DOS stored in phdocsnc use:

phbands.plot_fatbands(phdos_file=phdosnc, colormap="rainbow", alpha=0.4, units="cm-1");

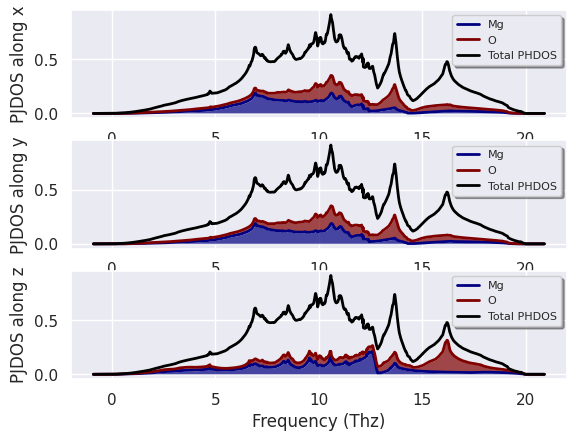

We can also plot the PJDOS summed over directions and atomic types without fatbands with the command:

phdosnc.plotly_pjdos_type();

The netcdf file contains the individual contributions to the total DOS for each atomic site and the three cartesian directions. So there are several quantities we can plot to understand the vibrational spectrum of our systems. For example, we can decide to sum over all atoms of the same type while keeping the dependence on the Cartesian direction:

phdosnc.plot_pjdos_cartdirs_type(units="Thz");

This analysis tells us that the peak at ~16 Thz mainly consists of oxygen vibrations along z. We could now extend this analysis by looking at the contributions arising from the different sites with:

#phdosnc.plot_pjdos_cartdirs_site(view="inequivalent", units="eV", stacked=True);

but we prefer to stop here and discuss other tools that can be used to analyze individual phonon modes.

Visualizing atomic displacements#

In you need to visualize the lattice vibrations in 3D to gain a better insight

about the nature of the phonon modes you may want to use the phononwebsite.

One can either convert the out_PHBST.nc produced by anaddb into json format

and upload it to the phononwebsite server or, alternatively, open the terminal and execute the AbiPy script:

abiview.py ddb out_DDB --phononwebsite

to automate the entire process (replace out_DDB with the name of your DDB file).

Note that there are other AbiPy methods that are quite handy if we need to investigate the nature of the phonon modes at a particular q-point without a 3D visualization tool. For example, it is possible to analyze the contribution given by the different types of atoms to the phonon displacements at a given q-point with:

phbands.plot_phdispl(qpoint=(0, 0, 0), tight_layout=True);

As expected the first three (acoustic) modes have zero frequency and the two atoms oscillate with the same amplitude. These modes indeed correspond to a rigid translation of the crystal hence the amplitude (and the direction) does not depend on the atomic site. The other three optical modes are (almost) degenerate, while LO-TO splitting should be present, but this is due to the fact that we are using the frequencies at the \(\Gamma\) point without the inclusion of the non-analytical term.

#phbands.plot_phdispl((0, 0, 0.1), is_non_analytical_direction=True, tight_layout=True);

To project the phonon displacements along the three cartesian directions, use:

phbands.plot_phdispl_cartdirs(qpoint=(0, 0, 0.0), tight_layout=True);

This plot confirms that the first three modes correspond to a rigid translation along x, y and z, respectively.

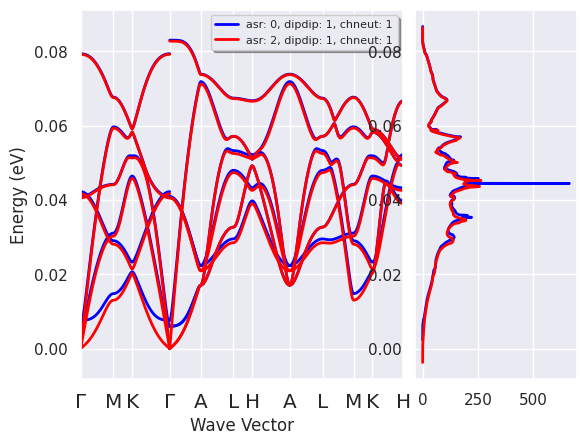

Analyzing the breaking of the acoustic sum rule#

Due to the invariance of the system under an infinitesimal rigid translation, the frequency of the lowest three modes at \(\Gamma\) should be zero. Unfortunately, all the terms that are evaluated on the real-space FFT mesh (e.g. \(V_{xc}\), non-linear core-correction) break this kind of translational invariance. The error depends on several factors: the density of the FFT mesh, pseudopotentials with hard model core charges, XC functional, etc.) Note that it is not always possible to reduce the error to zero by just increasing the convergence parameters but fortunately it is possible to restore the acoustic sum rule via the input variable.

One can easily compare the phonons bands obtained with different values of with:

asr_plotter = ddb.anacompare_asr()

This method invokes anaddb with different values of and returns a plotter object we can call to compare the phonon band structures:

asr_plotter.combiplot();

asr_plotter.combiplotly();

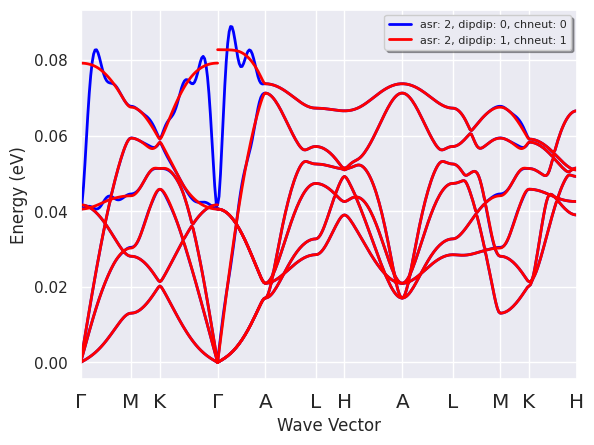

Now we can perform a similar test for the treatment of the non-analytical term in the \(q \rightarrow 0\) limit. We compute the phonon band dispersion for {{dipdip@anaddb} in [0, 1] and the compare the results on the same figure with the commands:

dipdip_plotter = ddb.anacompare_dipdip(nqsmall=0)

dipdip_plotter.combiplot();

dipdip_plotter.combiplotly();

The figure above shows that the (Fourier interpolated) bands obtained with dipdip = 0 have unphysical oscillations around the \(\Gamma\) point. These oscillation are due to the long-range behavior in real space of the interatomic force constants in polar semiconductors. The correct description of this long-range term without dipdip = 1 would require using an extremely dense q-point mesh in the DFPT calculation.

With {{dipdip@anaddb} = 1, on the other hand, we can model this long-range behavior in terms of a dipole-dipole interaction involving the Born effective charges and the macroscopic dielectric tensor. This allows us to decompose the full dynamical matrix into:

The analytical part of the dynamical matrix, \(D^{sr}(q)\), is short-ranged and can be Fourier-interpolated with a relatively coarse q-mesh. Then the model for the non-analytical term, \(D^{dip-dip}(q)\), is added back to the interpolated matrix to get the full dynamical matrix. This procedure solves the problem with the unphysical oscillations and is required to describe correctly the non-analytical behavior of the optical modes for \(q \rightarrow 0\).

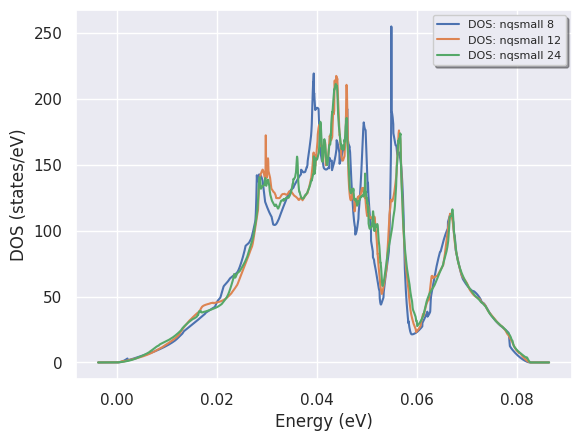

Computing DOS with different q-meshes#

Phonon DOS and derived quantities (e.g. thermodynamic properties) are sensitive to the BZ sampling and dense meshes may be required to converge the final results.

The method anacompare_phdos provides a simple interface to

compare phonon DOS computed with different \(q\)-meshes.

We only need to provide a list of integers (nqsmalls). Each integer defines the number of divisions used to

sample the smallest reciprocal lattice vector while the other two vectors are sampled such

that proportions are preserved.

To calculate three phonon DOS with increasing number of q-points use:

res = ddb.anacompare_phdos(nqsmalls=[8, 12, 24])

The return value is a named tuple with the phonon DOSes in res.phdoses while res.plotter is PhononDosPlotter. We can easily compare our results with:

res.plotter.combiplot();

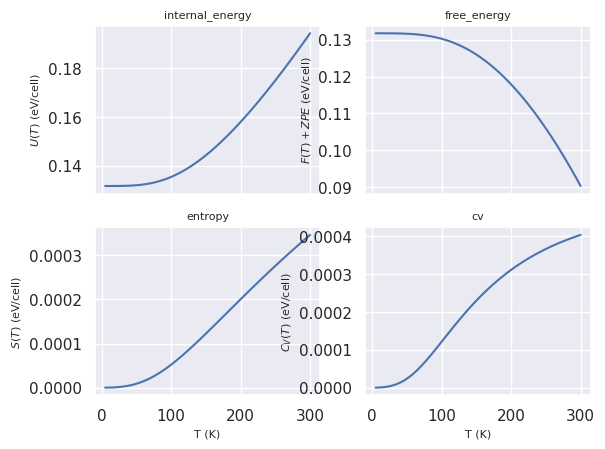

Thermodynamic properties in the harmonic approximation#

The thermodynamic properties of an ensemble of non-interacting phonons can be expressed in terms of integrals of the phonon DOS \(g(\omega)\) using:

where \(k_B\) is the Boltzmann constant. This should represent a reasonable approximation especially in the low-temperature regime in which anharmonic effects can be neglected.

Let’s plot the vibrational contributions to the thermodynamic properties as function of temperature \(T\):

phdos.plot_harmonic_thermo();

and the zero-point energy \(\dfrac{1}{2 N_q} \sum_{q\nu} \omega_{q\nu}\)

zpe = phdos.zero_point_energy

print("Zero-point energy", zpe, zpe.to("Ha"))

Zero-point energy 0.13171156295558706 eV 0.004840310661315252 Ha

To get the free energy for a range of temperatures in Kelvin degrees, use:

f = phdos.get_free_energy(tstart=10, tstop=100)

#f.plot();

Macroscopic dielectric tensor and Born effective charges#

Let us call anaddb to compute the electronic contribution to the macroscopic dielectric tensor, \(\epsilon^{\infty}_{\alpha\beta}\), and the Born effective charges \(Z^*_{\kappa,\alpha\beta}\):

emacro, becs = ddb.anaget_epsinf_and_becs(chneut=1)

Note the use of chneut to enforce charge neutrality.

emacro

| x | y | z | |

|---|---|---|---|

| x | 3.438497 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| y | 0.000000 | 3.438497 | 0.000000 |

| z | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 3.499416 |

becs

| element | site_index | frac_coords | wyckoff | xx | yy | zz | xy | xz | yx | yz | zx | zy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Mg | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | 1.98721 | 1.98721 | 2.10659 | 0.0 | 2.565407e-24 | 0.0 | 1.629252e-23 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | O | 1 | [0.33333333333333, 0.66666666666667, 0.5] | 1d | -1.98721 | -1.98721 | -2.10659 | 0.0 | -2.565407e-24 | 0.0 | -1.629252e-23 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

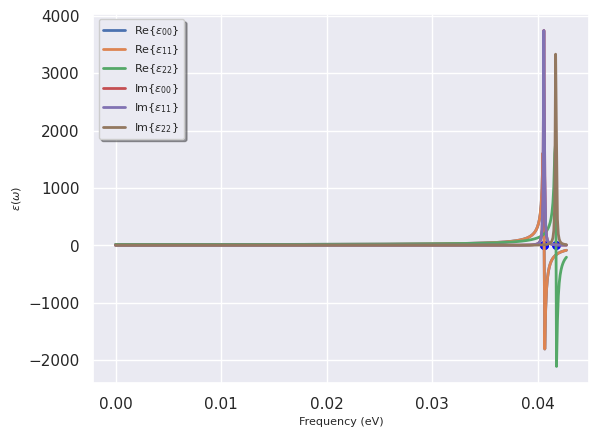

In the computation of the low-frequency (infrared) dielectric tensor, \(\epsilon^{0}_{\alpha\beta}\), one has to include the response of the ions, whose motion will be triggered by the electric field. One can show that:

where \(\omega^{\Gamma}_m\) are the phonon frequencies at the center of the BZ and \(S_{m,\alpha\beta}\) is the so-called mode-oscillator strength tensor that depends on the phonon displacement and the Born effective charges.

To compute the dielectric tensor using the data stored in the DDB file, use:

dtgen = ddb.anaget_dielectric_tensor_generator()

# call print to get useful information

print(dtgen)

================================= Structure =================================

Full Formula (Mg1 O1)

Reduced Formula: MgO

abc : 2.908638 2.908638 2.656848

angles: 90.000000 90.000000 120.000000

pbc : True True True

Sites (2)

# SP a b c

--- ---- -------- -------- ---

0 Mg 0 0 0

1 O 0.333333 0.666667 0.5

Abinit Spacegroup: spgid: 1, num_spatial_symmetries: 12, has_timerev: True, symmorphic: False

============================ Oscillator strength ============================

Real part in Cartesian coordinates. a.u. units; 1 a.u. = 253.2638413 m3/s2. Set to zero below 1.00e-06.

xx yy zz yz xz xy

mode

0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

3 0.00022453328281351966 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

4 0.0 0.00022453328281351966 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

5 0.0 0.0 0.0002523207013218457 0.0 0.0 0.0

============================= Dielectric Tensors =============================

Electronic dielectric tensor (eps_inf) in Cartesian coordinates. Set to zero below 1.00e-03.

x y z

x 3.438497 0.000000 0.000000

y 0.000000 3.438497 0.000000

z 0.000000 0.000000 3.499416

Zero-frequency dielectric tensor (eps_zero) in Cartesian coordinates. Set to zero below 1.00e-03.

x y z

x 13.101919 0.000000 0.000000

y 0.000000 13.101919 0.000000

z 0.000000 0.000000 13.779005

To compute the tensor for a given frequency:

e0 = dtgen.tensor_at_frequency(0)

print(e0)

[[ 1.31018620e+01+0.02381961j 2.54893071e-16+0.j

1.47502725e-25+0.j ]

[ 0.00000000e+00+0.j 1.31018620e+01+0.02381961j

-2.55482215e-25+0.j ]

[-3.68756813e-25+0.j -1.27741107e-25+0.j

1.37789478e+01+0.02465278j]]

To plot the frequency dependence with a damping factor of 1e-4 eV (phonon linewidth):

dtgen.plot(w_max=None, gamma_ev=1e-4, component='diag', units='eV');

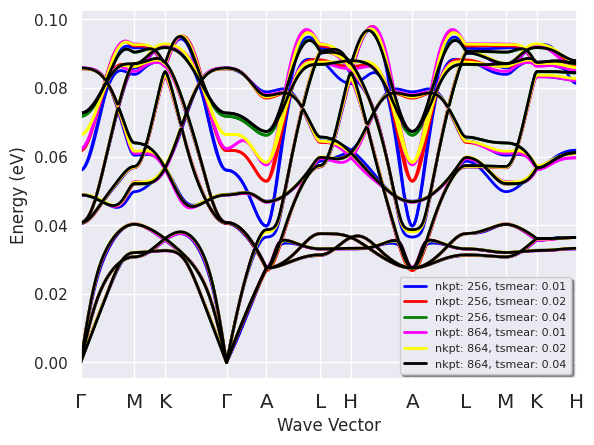

Using DdbRobot to perform convergence studies#

A DdbRobot receives a list of DDB files and provides methods

to construct pandas dataframes

and analyze the results of multiple calculations.

DdbRobots, in particular, are extremely useful to study the convergence of the phonon frequencies with respect to some computational parameters e.g. the number of k-points and the electronic smearing in metallic systems.

In this example, we are interested in the effect of the k-point sampling and the smearing parameter

on the vibrational properties of magnesium diboride.

\(MgB_2\) is a metallic system with a critical temperature of 39 K that is the highest among conventional

(phonon-mediated) superconductors.

We use precomputed DDB files obtained by running GS+DFPT calculations with different values

of nkpt and tsmear.

Let’s build our DdbRobot object with:

import os

paths = [

#"mgb2_444k_0.01tsmear_DDB",

#"mgb2_444k_0.02tsmear_DDB",

#"mgb2_444k_0.04tsmear_DDB",

"mgb2_888k_0.01tsmear_DDB",

"mgb2_888k_0.02tsmear_DDB",

"mgb2_888k_0.04tsmear_DDB",

"mgb2_121212k_0.01tsmear_DDB",

"mgb2_121212k_0.02tsmear_DDB",

"mgb2_121212k_0.04tsmear_DDB",

]

paths = [os.path.join(abidata.dirpath, "refs", "mgb2_phonons_nkpt_tsmear", f) for f in paths]

robot = abilab.DdbRobot.from_files(paths)

robot

- ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/mgb2_phonons_nkpt_tsmear/mgb2_888k_0.01tsmear_DDB

- ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/mgb2_phonons_nkpt_tsmear/mgb2_888k_0.02tsmear_DDB

- ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/mgb2_phonons_nkpt_tsmear/mgb2_888k_0.04tsmear_DDB

- ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/mgb2_phonons_nkpt_tsmear/mgb2_121212k_0.01tsmear_DDB

- ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/mgb2_phonons_nkpt_tsmear/mgb2_121212k_0.02tsmear_DDB

- ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/mgb2_phonons_nkpt_tsmear/mgb2_121212k_0.04tsmear_DDB

The abicomp.py script provides a command line interface to build robots from a list of files/directories given as arguments

The DDB files are now stored in the robot with a label constructed from the file path. These labels, however, are not very informative. In principle we would like to have a label that reflects the value of (nkpt, tsmear) also because these labels will be used to generate the labels in our plots.

Let’s fix it with a function that recomputes the labels from the metadata available in ddb.header:

function = lambda ddb: "nkpt: %s, tsmear: %.2f" % (ddb.header["nkpt"], ddb.header["tsmear"])

robot.remap_labels(function);

robot

- nkpt: 256, tsmear: 0.01

- nkpt: 256, tsmear: 0.02

- nkpt: 256, tsmear: 0.04

- nkpt: 864, tsmear: 0.01

- nkpt: 864, tsmear: 0.02

- nkpt: 864, tsmear: 0.04

We are usually interested in the convergence behavior with respect to one or two parameters of the calculations. Let’s build a pandas dataframe with the most important parameters extracted from the DDB header:

robot.get_params_dataframe()

| nkpt | nsppol | ecut | tsmear | occopt | ixc | nband | usepaw | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nkpt: 256, tsmear: 0.01 | 256 | 1 | 35.0 | 0.01 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| nkpt: 256, tsmear: 0.02 | 256 | 1 | 35.0 | 0.02 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| nkpt: 256, tsmear: 0.04 | 256 | 1 | 35.0 | 0.04 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| nkpt: 864, tsmear: 0.01 | 864 | 1 | 35.0 | 0.01 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| nkpt: 864, tsmear: 0.02 | 864 | 1 | 35.0 | 0.02 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| nkpt: 864, tsmear: 0.04 | 864 | 1 | 35.0 | 0.04 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

Now we tell the robot to invoke anaddb to compute the phonon bands for all DDB files.

Since we are not interested in the phonon DOS, nqsmall is set to 0

r = robot.anaget_phonon_plotters(nqsmall=0)

Now we can plot all the phonon band structures on the same figure with:

r.phbands_plotter.combiplot();

The plot is a bit crowded. Still, it is clear that there are portions of the vibration spectrum that are quite sensitive to the values of (nkpt, tsmear).

In metals, it’s common to analyze the convergence of the physical properties by plotting the results as function of the k-point sampling for fixed value of tsmear. Let’s do something similar for the phonon band structures with the command:

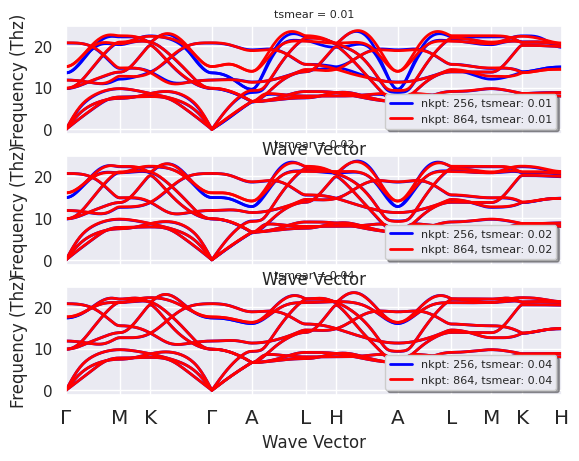

r.phbands_plotter.gridplot_with_hue("tsmear", units="Thz");

Each panel now shows the phonon dispersion computed with different k-point samplings at fixed tsmear.

The results obtained with the largest broadening (0.04 Ha) seem to be converged but remember that the “converged” result are in principle obtained in the limit \(nkpt \rightarrow +\infty\) and \(tsmear\rightarrow 0\) (well it’s not always possible to reach the mathematical limit so we should try to understand what happens to our observables when we are approaching this limit and if it’s possible to find values of (nkpt, tsmear) that are “close enough” to convergence).

The middle panel reveals that there are two branch (6-7, Python indexing) along \(\Gamma-A\) that are quite sensitive to the sampling of the Fermi surface and this picture is confirmed by the first panel obtained with the lowest value of the electronic broadening.

This analysis tells us two things:

We should analyze in more detail the convergence behavior of these specific branches wrt (nkpt, tsmear) to make sure our results are really converged

The strong variations observed in that particular region of the phonon spectrum could represent the signature of an important coupling between these vibrational modes and the electrons on the Fermi surface…

If you now dig a bit into the scientific literature, you will find that this is the famous \(E_{2g}\) branch (in-plane oscillations of the two B atoms, twofold degenerate at \(\Gamma\)) that plays an important role in explaining the superconducting behavior of \(MgB_2\).

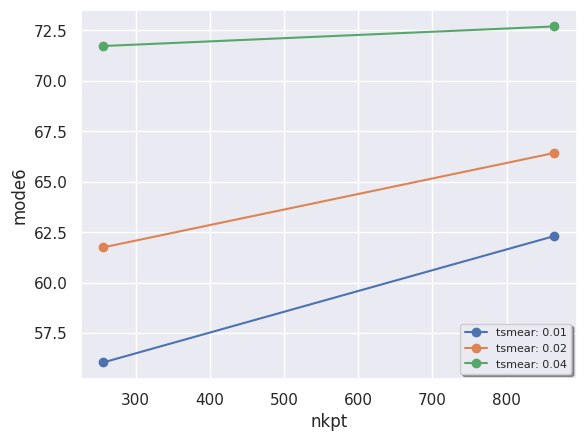

Let’s look in more details at the softening at the \(\Gamma\) point.

We start by calling get_phdata_at_qpoint to construct a pandas dataframe

with the phonon frequencies in meV and the parameters of the calculation:

data = robot.get_phdata_at_qpoint(qpoint=(0, 0, 0), with_geo=False)

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmplkgw6nsx

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmpqlhce0wh

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmp6sl2qxr9

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmpk271f17y

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmpk609jff5

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmpdet7lt0m

and use seaborn to produce a scatter plot in which the color of the points depends on tsmear:

robot.plot_xy_with_hue(data.ph_df, x="nkpt", y="mode6", hue="tsmear");

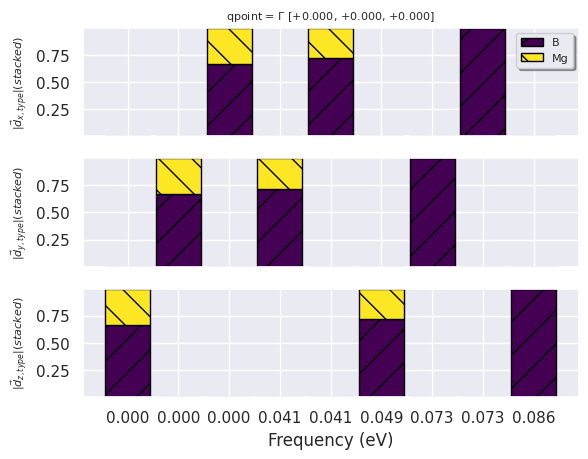

A DDbRobot is essential a dictionary of DdbFiles, and we can therefore reuse the DdbFile methods to call anaddb. For example, we mentioned that the two degenerate \(E_{2g}\) modes at \(\Gamma\) involve in-plane oscillations of the two Mg atoms. Let’s check this with:

key = "nkpt: 864, tsmear: 0.04"

gamma_point = (0, 0, 0)

phbands_gamma = robot[key].anaget_phmodes_at_qpoint(gamma_point, dipdip=0, lo_to_splitting=False)

phbands_gamma.plot_phdispl_cartdirs(gamma_point);

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmp8ab9p8q_

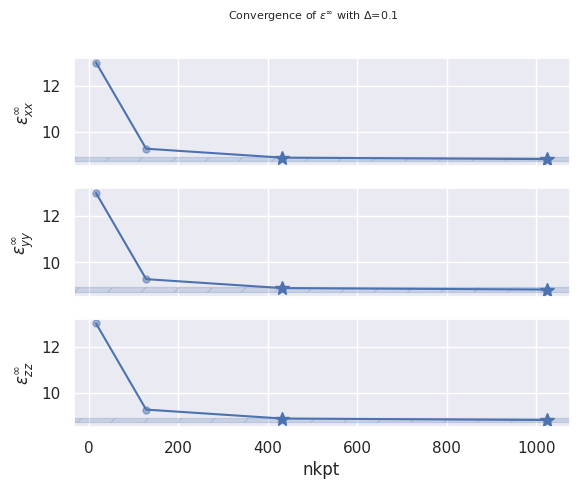

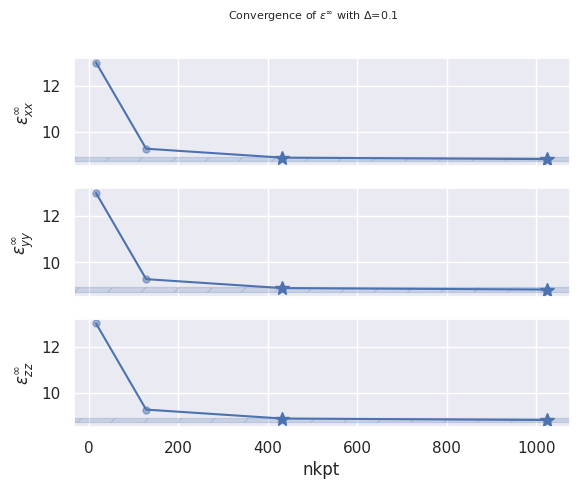

How to analyze the converge of \(\epsilon^0\), \(\epsilon^\infty\) and Born effective charges#

Let’s assume we have computed the dielectric properties and the Born effective charges for a given

system with different k-meshes, and we want to analyze the convergence of the results.

Also in this case, the DdbRobot provides methods to automate most of the boring work.

As usual, we start by creating a robot from a list of paths to DDB files. Here we use three different files produced with 2x2x2, 4x4x4 and 8x8x8 k-meshes.

paths = [

"AlAs_222k_DDB",

"AlAs_444k_DDB",

"AlAs_666k_DDB",

"AlAs_888k_DDB",

]

paths = [os.path.join(abidata.dirpath, "refs", "alas_eps_and_becs_vs_ngkpt", f) for f in paths]

alas_robot = abilab.DdbRobot.from_files(paths)

Now we call anacompare_epsinf to create a pandas Dataframe with the upper triangle

of the \(\epsilon_{ij}^\infty\) dielectric tensor (Voigt notation) and we add the number of k-points

in the IBZ to the table to facilitate the analysis:

epsinf_data = alas_robot.anacompare_epsinf(ddb_header_keys="nkpt")

epsinf_data.df

| xx | yy | zz | yz | xz | xy | formula | chneut | nkpt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12.996449 | 12.996449 | 12.996449 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 16 |

| 1 | 9.268431 | 9.268431 | 9.268431 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 128 |

| 2 | 8.881665 | 8.881665 | 8.881665 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 432 |

| 3 | 8.818122 | 8.818122 | 8.818122 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 1024 |

epsinf_data.plot_conv("nkpt", abs_conv=0.1)

A similar approach can be used to analyze \(\epsilon_{ij}^0\)

r = alas_robot.anacompare_eps0(ddb_header_keys="nkpt")

r.df

| xx | yy | zz | yz | xz | xy | formula | asr | chneut | nkpt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15.205414 | 15.205414 | 15.205414 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| 1 | 10.839420 | 10.839420 | 10.839420 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 2 | 1 | 128 |

| 2 | 10.423517 | 10.423517 | 10.423517 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 2 | 1 | 432 |

| 3 | 10.352747 | 10.352747 | 10.352747 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 2 | 1 | 1024 |

Analyzing the convergence of the Born effective charges is a bit more complicated because now we have a tensor for each atom in the unit cell:

becs_data = alas_robot.anacompare_becs(ddb_header_keys="nkpt")

becs_data.df

| element | site_index | frac_coords | wyckoff | xx | yy | zz | xy | xz | yx | yz | zx | zy | formula | chneut | nkpt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | 2.344626 | 2.344626 | 2.344626 | 0.0 | 3.443860e-19 | 0.0 | 3.443860e-19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 16 |

| 2 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | 1.998460 | 1.998460 | 1.998460 | 0.0 | 4.579838e-20 | 0.0 | 4.579838e-20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 128 |

| 6 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | 1.967000 | 1.967000 | 1.967000 | 0.0 | 1.580002e-20 | 0.0 | 1.580002e-20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 1024 |

| 4 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | 1.972550 | 1.972550 | 1.972550 | 0.0 | 1.519421e-19 | 0.0 | 1.519421e-19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 432 |

| 3 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -1.998460 | -1.998460 | -1.998460 | 0.0 | -4.579838e-20 | 0.0 | -4.579838e-20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 128 |

| 1 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -2.344626 | -2.344626 | -2.344626 | 0.0 | -3.443860e-19 | 0.0 | -3.443860e-19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 16 |

| 5 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -1.972550 | -1.972550 | -1.972550 | 0.0 | -1.519421e-19 | 0.0 | -1.519421e-19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 432 |

| 7 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -1.967000 | -1.967000 | -1.967000 | 0.0 | -1.580002e-20 | 0.0 | -1.580002e-20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Al1 As1 | 1 | 1024 |

becs_data.plot_conv("nkpt", abs_conv=0.1);

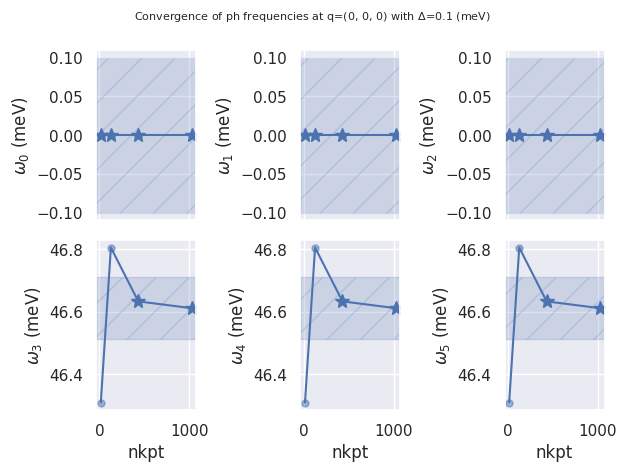

A similar API can be used to analyze the convergence of the phonon frequencies for a given q-point:

ph_data = alas_robot.get_phdata_at_qpoint(qpoint=(0, 0, 0))

ph_data.ph_df

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmpizanrtww

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmpl4mhg4ul

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmp97f3dhb1

Calculation completed. Anaddb results available in: /tmp/tmp2miam3jt

| mode0 | mode1 | mode2 | mode3 | mode4 | mode5 | nkpt | nsppol | ecut | tsmear | ... | beta | gamma | a | b | c | volume | abispg_num | spglib_symb | spglib_num | spglib_lattice_type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/alas_eps_and_becs_vs_ngkpt/AlAs_222k_DDB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 46.309323 | 46.309323 | 46.309323 | 16 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ... | 60.0 | 60.0 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 44.247584 | 1 | F-43m | 216 | cubic |

| ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/alas_eps_and_becs_vs_ngkpt/AlAs_444k_DDB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 46.805652 | 46.805652 | 46.805652 | 128 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ... | 60.0 | 60.0 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 44.247584 | 1 | F-43m | 216 | cubic |

| ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/alas_eps_and_becs_vs_ngkpt/AlAs_666k_DDB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 46.633272 | 46.633272 | 46.633272 | 432 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ... | 60.0 | 60.0 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 44.247584 | 1 | F-43m | 216 | cubic |

| ../abipy/abipy/data/refs/alas_eps_and_becs_vs_ngkpt/AlAs_888k_DDB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 46.611452 | 46.611452 | 46.611452 | 1024 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ... | 60.0 | 60.0 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 3.970101 | 44.247584 | 1 | F-43m | 216 | cubic |

4 rows × 27 columns

ph_data.plot_ph_conv("nkpt", abs_conv=0.1); # meV units.

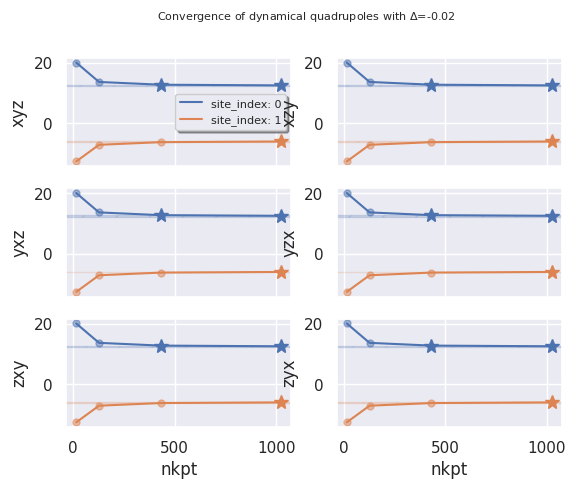

If the DDB contains dynamical quadrupoles, a similar dataframe with the tensor

elements is automatically built and made available in ph_data.dyn_quad_df.

ph_data.dyn_quad_df

| element | site_index | frac_coords | wyckoff | xxx | xxy | xxz | xyx | xyy | xyz | ... | spglib_num | spglib_lattice_type | nkpt | nsppol | ecut | tsmear | occopt | ixc | nband | usepaw | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | -2.243078e-08 | -2.415429e-09 | -2.415429e-09 | -2.415429e-09 | 0.0 | 20.138754 | ... | 216 | cubic | 16 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 1 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -1.088089e-07 | -3.286597e-09 | -3.286597e-09 | -3.286597e-09 | 0.0 | -12.586486 | ... | 216 | cubic | 16 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 2 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | -3.570443e-08 | -2.209766e-08 | -2.209766e-08 | -2.209766e-08 | 0.0 | 13.726256 | ... | 216 | cubic | 128 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 3 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -9.438199e-08 | -4.579025e-08 | -4.579025e-08 | -4.579025e-08 | 0.0 | -7.083927 | ... | 216 | cubic | 128 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 4 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | -3.065937e-08 | -1.837058e-08 | -1.837058e-08 | -1.837058e-08 | 0.0 | 12.813336 | ... | 216 | cubic | 432 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 5 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -1.021827e-07 | -4.617914e-08 | -4.617914e-08 | -4.617914e-08 | 0.0 | -6.205913 | ... | 216 | cubic | 432 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 6 | Al | 0 | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | 1a | -2.744198e-08 | -1.517858e-08 | -1.517858e-08 | -1.517858e-08 | 0.0 | 12.588533 | ... | 216 | cubic | 1024 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 7 | As | 1 | [0.25, 0.25, 0.25] | 1d | -9.765058e-08 | -4.402063e-08 | -4.402063e-08 | -4.402063e-08 | 0.0 | -5.989993 | ... | 216 | cubic | 1024 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

8 rows × 52 columns

A negative value of abs_conv is interpreted as relative convergence.

ph_data.plot_dyn_quad_conv("nkpt", abs_conv=-0.02);